Aberdeen to honour Scot

who has been US hero

for 228 years

Press & Journal

29/03/2005

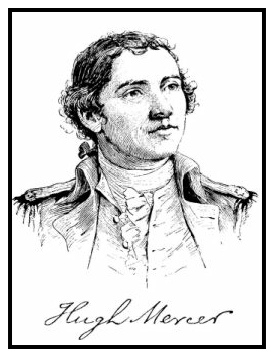

HE WAS one of George Washington's greatest generals and led Revolutionary forces across the Delaware River in one of the defining battles that helped changed the shape of America.

Historians argue that, had it not been for his untimely and grisly death at the Battle of Princeton in 1777, Hugh Mercer, born in Aberdeenshire, would have been a greater leader than Washington and would rank as one of the greatest American heroes of all time.

Yet the military genius whose exploits turned the tide in the Revolutionary War only settled in America after fleeing his native Scotland a wanted man, having fought with Bonnie Prince Charlie at Culloden in 1746.

Now, 228 years after he was bayoneted to death by British soldiers, Mercer is to be recognised by his native city, which until recently had been unaware of his existence, let alone his immense contribution to American Independence.

Chris Croly, of Aberdeen city council's archaeological unit, said: "He was brought to our attention by a member of the public. There are so many great and good from the city that some have simply slipped through the net and not been remembered.

"Hugh Mercer was one of these people. He studied medicine at Marischal College in Aberdeen, joined the 1745 Rebellion after graduating then fled to America. His stock has always been high in the United States and it is great that we are remembering someone who had to flee this country."

Mr Croly said a commemorative plaque in Mercer's honour is to be unveiled in the quadrangle at Marischal College, where the young rebel spent his student life.

The council asked the public to come up with suggestions about anyone who might be worthy of a plaque and Mercer's name was put forward.

The scant knowledge in Scotland about Mercer's life and achievements contrasts sharply with the hero status he enjoys in America. Mercersburg, a town in Pennsylvania and the birthplace of President James Buchanan, is named after him and there are Mercer Counties in his honour in seven US states.

Statues of him have been erected in Philadelphia and the city of Fredericksburg, Virginia, where Mercer set up a medical practice and where he and Washington planned the early stages of the Revolutionary War. The Hugh Mercer Apothecary Shop in Fredericksburg is preserved and run as a historic site.

He was the great-grandfather of songwriter Johnny Mercer who wrote classics such as Moon River and That Old Black Magic and the great-great-grandfather of General George Patton, known as "Old Blood and Guts".

It is a far cry from his boyhood in rural Aberdeenshire. Born in 1725 at the manse at the village of Pitsligo, he grew up in the fishing port of Rosehearty.

A year after graduating from Marischal College he joined with Bonnie Prince Charlie's army and was an assistant surgeon at the Battle of Culloden.

On the run from the Hanoverian forces he sailed for America and settled in Philadelphia.

He distinguished himself during the French and Indian War when, despite being badly injured, he walked over 100 miles to safety and was honoured for his bravery. It was during this conflict he first met Washington and the two men settled in Fredericksburg.

"Washington made him a brigadier general at the start of the Revolutionary War and he was so highly respected as a soldier that many people feel he was as good a general as Washington, if not better.

"Unfortunately he died early in the war and he has become something of a forgotten hero," said Genevieve Bugay, site manager of the Hugh Mercer Apothecary Shop.

"It is the opinion of most biographers that he would have been greater than Washington. He led troops across the Delaware at the famous Battle of Trenton and shortly afterwards fought at Princeton where he died.

"These battles were critical to American history because the army badly needed a victory otherwise Washington would have lost. Hugh Mercer is something of a hero in these parts, and I am delighted that he is being recognised in Aberdeen."

Allan Maclnnes, professor of history at Aberdeen University, said: "We should not feel guilty about not knowing him here, we are just beginning to unravel a lot of people who went overseas and became famous. Historical research is opening up and revealing these people."

Mercer lived for nine days before dying of the wounds he suffered at Princeton. His funeral in Philadelphia was attended by more than 30,000 mourners.

THREE AMERICAN GENERALS

Scottish Ancestry corrected

Clan Munro Magazine 2000

This article by R.W. MUNRO explains how an American general's visit to Scotland in 1981 led to a re-examination of the Scottish ancestry of his family. Some of the information given in earlier biographies of Gen. Hugh Mercer can now be corrected.

IF a genealogist or family historian finds it impossible to accept an ancestral line hitherto adopted as correct, it is much more satisfactory for all concerned if it can be replaced by a well-founded alternative. This is the story of a search which incidentally brought to light some facts about a little-known fellow clansman who held public office in the north of Scotland more than 300 years ago, and was apparently not afraid to clash on matters of principle with the authorities of his day.

For some reason there has long been doubt and misinformation about Anne Monro, who was the mother of General Hugh Mercer (1726-77), of Fredericksburg, Virginia, a native of Scotland, who became one of the heroes of the American War of Independence, fatally wounded in Washington's victory at Princeton. As Anne was also the progenitor of at least two other Generals of the U.S. Army (the late Gen. George S. Patton and his son Major-General G.S. Patton), it is perhaps worth putting the record straight of their Munro ancestry.

Anne Monro - for so the clan name was often spelt in those days in Scotland - was the wife of William Mercer, parish minister of Pitsligo in Aberdeenshire. Sometimes she is thought to have been the daughter of Sir Robert Munro of Foulis, chief of the clan, killed at the battle of Falkirk in January 1746; and to add to the confusion, some writers have given the name of her husband as William Row. As neither of these statements is correct, although both are I believe in print, and have been quoted to me more than once, a meeting with General and Mrs Patton some years ago revived my interest in the problem and set me searching for the truth.

This search led me to investigate what was known in the public records about Andrew Monro, who as Sheriff Clerk of Moray was the principal official in the court of the highest judge in this Scottish county or shire, and therefore a key man in the local administration of justice.

Andrew Monro appears on record as Sheriff Clerk of Moray when, at Elgin on 8 June 1676, he acted as cautioner (surety) for Hugh Monro, writer or lawyer in Elgin (then 22 years of age or thereby), on his admission as notary public.1 This was a time of deep religious controversy in Scotland, and it was apparently as a result of his disapproval of the measures taken by the King's government to suppress the Presbyterian system of church organisation that Andrew was deprived of or resigned his office, at least temporarily.

Under the Test Act of 1681, all holders of public office, civil, ecclesiastical or military, had to take a new oath of allegiance. By this they would promise to maintain the Protestant religion as then established without seeking any change or alteration in it, and to accept the king as supreme governor of the realm in spiritual as well as temporal affairs. No record has been found of Andrew Monro having taken this oath, although the Test Act remained law until the Presbyterian system was established in Scotland by the Revolution of 1689/90. With Charles II's Catholic brother and heir, James Duke of York, as his his High Commissioner in Scotland. After James became king on Charles's death on 6 February 1685, there was considerable disaffection in various parts of Scotland.

At the end of 1684 the Scottish Privy Council appointed several commissions to visit certain areas and prosecute all persons guilty of neglect or irregularity in church ordinances and other crimes. For this purpose the 'bounds betwixt Spey and Ness' were allocated to the Earl of Erroll, the Earl of Kintore and Sir George Monro of Culrain, who were based at Elgin from 22 January to 11 February 1685. A report of their proceedings, sent to the Privy Council in Edinburgh early in March, and the council's own records, show that the royalist Sir George's chief and nephew (Sir John Munro of Foulis) and some of his tenants and clansmen in Easter Ross were among the 'disaffected'.2

Andrew Monro, described as 'late sheriff-clerk and commissary clerk of Elgin', and his spouse Barbara Cuming were among many people accused of 'ecclesiastical disorders' (19 January), 5 being among the 'dishaunters of ordinances' in Elgin parish (27 January) and classed as 'delinquents'. But it seems that they, or perhaps the commissioners, may have wavered: it was reported in early February that Andrew 'now keeps the kirk' and he and his wife 'will live regular', that they were making ready to go to Jersey and had taken the bond of peace;3 but within only a few days Andrew, along with Donald Monro baker in Elgin and many others, refusing to take the oath of allegiance to the new king, were sentenced to be banished from the kingdom (11 February).

King James protected his co-religionists and allowed a measure of toleration to presbyterians, but even his 'indulgences' led to widespread division among his people. Andrew seems to have been allowed to remain in Scotland and to resume his office as Sheriff Clerk, for he appears with that designation in Elgin town council's minutes (12 December 1687) as well as after the Revolution, and is said to have held office until 1703.

It is not known how long Andrew and his wife survived these ordeals, but they had three daughters who all married ministers of the (presbyterian) Church of Scotland. Grizel (or Grissel) married in 1702 Alexander Shaw, minister of Edinkillie; Anne married in June 1723 William Mercer, minister of Pitsligo; and Margaret married Hugh Anderson, minister of Rosemarkie and later of Drainie or Kineddar.4 Anne was the mother of Hugh Mercer, born in January 1726; she died in 1768, her sister Grizel in 1769, and Margaret in 1749.

Notes

1 National Archives of Scotland, MS ref. NP 2/11.

2 Sir George was of 'different principles' from his elder brother Robert Munro of Obsdale, who succeeded to Foulis in 1651 (Scotland and the Protectorate, ed. C.H. Firth, 88, 235-6).

3 Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, 3rd series, vol. x.

4 Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae, ed Hew Scott, revised edn., vi 419, 235,383; vii 22.